The Right to Vote

February 11, 2016 § 6 Comments

With such a heated presidential election upon us, voting has been a popular topic of conversation in our house. My eight year old is trying to make sense of the candidate names he has heard; and he repeatedly asks my husband and I who we “want to win” this November, convinced with that blind, beautiful eight-year-old innocence that his parents’ choice must be the right one. (I’m tempted to blow his mind by telling him that his dad and I might each want someone different.)

With such a heated presidential election upon us, voting has been a popular topic of conversation in our house. My eight year old is trying to make sense of the candidate names he has heard; and he repeatedly asks my husband and I who we “want to win” this November, convinced with that blind, beautiful eight-year-old innocence that his parents’ choice must be the right one. (I’m tempted to blow his mind by telling him that his dad and I might each want someone different.)

The right to vote may be one that many of us Americans take for granted today (much like trying on shoes at a store—see last year’s post for Black History Month); and yet, it also seems to inspire a certain awe in our children. Or at least it did in me when I was young. My mother would take me along when she voted in major elections. We’d wait in line, hand in hand, and then part of me would cringe in betrayal when at last it was her turn and she would pull the curtain closed around the voting booth, leaving her on one side and me on the other. I would strain to see her shadow beneath the curtain, trying to make heads or tails of what she was doing in there. “Can’t I come in with you?” I’d lament. “Isn’t it unsafe to leave me out here all alone?” I’d try. But her answer was always the same: “Voting is private. What I do in here is nobody’s business but my own.” That night, I’d try harassing my father: “But you did vote for who you said you were going to, right?” “That’s for me to know,” my dad would reply, the corners of his mouth turning up slightly.

Each time I vote, I think of the reverence that I attached to the voting process from such an early age. I wear my “I Voted!” sticker proudly. I talk to my children about how exciting it feels to cast my vote, to have a say in the rules-making of our country; and I take them with me when I can. And yet, I want them to understand that, while we have called ourselves a democracy for centuries, the history surrounding voting in this country has often been hypocritical, unjust, and deeply painful. For poor white men who didn’t own property. For women. For Native Americans. For African Americans. And for countless other marginalized groups across our history.

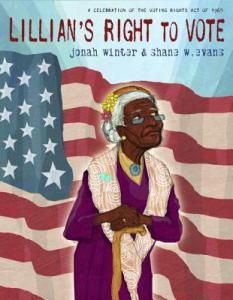

Browsing our local bookstore a few weeks ago, I quickly fell in love with Jonah Winter and Shane W. Evans’ new picture book, Lillian’s Right to Vote: A Celebration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Ages 6-12); and my excitement only grew after sharing it with my children. Written on the fiftieth anniversary of Lyndon Johnson signing into law the Voting Rights Act—which for the first time in history ensured that the voting rights of African Americans were protected by federal law—the book opens with a 100-year-old black woman on her way to vote. As she climbs the (literally) steep hill to the polling center, she reflects on the (metaphorically) steep hill that her people have climbed to get to this point, connecting her own family history with pivotal events in American history.

What I love most about this book—apart from Winter’s soaring prose and Evans’ emotionally charged mixed-media illustrations—is the compelling chronological presentation. It reads as a kind of lyrical—albeit highly abridged—timeline of black history in America (and what elementary child doesn’t love a good timeline?). Recently, it struck me that, while we may talk to our children about historical time periods, like slavery and the Civil Rights Movement, we usually do so in isolation. Just a few weeks ago at dinner, the topic of the Civil War came up. JP blurted out, “Mommy, the slaves must have been so happy when the war ended and they knew they were free.” I paused. “Well, let’s talk about that,” I said. And then we discussed what it was like to start a life with no money, no rights, no job, no education, and little to no respect, until JP said, “Oh, right, because all that was before the Civil Rights Movement.” A light bulb had gone off. Connections. Bringing together what we have learned: this is our job as parents and educators, and books can be among our greatest tools.

Lillian is a fictional character, although the Afterward at the end of the book reveals that she is inspired by an actual woman named Lillian Allen, granddaughter of a slave, who not only voted at age 100 for Barack Obama, our first African American president, but also passionately campaigned to encourage others to vote during that time.

This is where I have to pause to sing the praises of the book’s cover. How often do we see an elderly person depicted in children’s books, much less on the cover? My five-year-old daughter is fascinated with old people. She is fortunate to have two living great-grandmothers, and one of them was just here at Christmas. A few days after she left, Emily announced, “Great Gock is my favorite person in the family. She is so, so, so wise, because she has lived for practically forever, and can I tell you something? I don’t think she’s ever going to die.”

When we gaze at Lillian—and oh, the art is beautiful—we see dark creases across her face, silvery white hair, and long bony fingers. Her very body exudes age. And history. And wisdom. Lillian’s journey through the ghosts of history begins at a time when only rich white men were allowed to vote. It begins with a vision of her great-great-grandparents, standing on an auction block, holding their baby and waiting to be sold into slavery. The art is staggering and horrifying at the same time: the man is completely naked, his wrists bound. Here, as on every page, there is just enough text to invite an older child’s questions and initiate discussion with a trusting adult—yet not enough to confuse or frighten off younger ones. My eight year old wanted to talk about every single thing he noticed. My five year old just listened and took things in. That’s typical for where they both are.

We then meet Lillian’s great grandfather, Edmund, who grows up in slavery and witnesses both the end of the Civil War and the passing of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, which says that Americans can no longer be denied the right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition to servitude.” Edmund’s wife goes with him to the polling place—except that she, being a woman, cannot vote. Cue more discussion.

But a happy ending for all black men? Not at all. Here’s where things start to get fascinating, especially if you are a child who assumes that just because the law decrees something, it must be true. Lillian reflects on her grandfather, who twenty years later is charged an exorbitant poll tax that he can’t possibly pay. He is denied his chance at voting. And then there’s Lillian’s uncle Levi, who at a polling booth is asked outrageous questions—like “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?”—and then turned away when he can’t come up with an adequate answer. “But how could anyone figure that out?!” JP shouted out in horror. (Indeed.)

And then there’s Lillian’s own experience: first, as a little girl, being driven away by an angry mob when she goes with her mother to register to vote in 1920, after the Nineteenth Amendment has been passed to allow women the right to vote. That same mob later that night sets fire to a cross on her parents’ lawn (“something she will always see”), a signal to them that they—by nature of their skin color—are somehow outside the laws that promise to protect them.

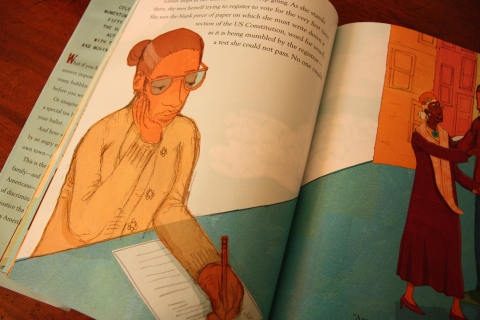

Years later, as a young woman, Lillian attempts to register to vote and is tested on the US Constitution, asked to write from memory word for word, a test that one again virtually no one could pass.

These injustices don’t just blow my children’s minds. They blow my mind. How could so many officials, so many cities, so many states, have gotten away with turning their backs on the law, with interpreting it to further their own bigotry? We watch as our children trust in things bigger than themselves—in systems and laws and figures of authority—but what happens when all that comes crashing down? How do we show them that they can stand up for themselves amidst this kind of adversity?

The Civil Rights Movement is one brilliant, though at times exceedingly brutal, answer. As Lillian walks up the hill to vote in 2015, she remembers the thousands who put one foot in front of the other through rain and wind to protest peacefully the unlawful and inhumane obstacles denying African Americans the right to vote. The three attempted marches from Selma to Montgomery are discussed, culminating in President Johnson’s famous speech, which echoed the words of Martin Luther King Jr.: All of us…must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome. (Check out this older post about another chronologically organized book, which highlights the role of the “We Shall Overcome” lyrics in human rights history.)

At last, as per the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which guarantees every American citizen the right to vote, Lillian herself is finally able to cast a poll, to make her voice heard alongside white, black, rich, poor, male, female, and everything in between. We watch as Lillian—fifty years later and now one hundred years old—remembers that moment in 1965, standing before the voting booth. Her younger, more elegant self is juxtaposed against her older, now stooped body, an arresting visual that reminds us how we take our former selves with us, folding them into ourselves and holding on to the memories that have made us who we are.

We are by this point so emotionally invested in Lillian’s story that it almost takes our breath away to turn to the final page, where we find a hand with a single outstretched finger hovering over a depressed lever. One simple movement, loaded with meaning and history and significance.

It was a long uphill battle to get here, and this lovely book gives our children a small taste of what that means. Those old enough to digest the Afterward, however, will learn that this is by no means the end of the struggle. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and, in the process, opened the door for individual states to mandate different voting requirements, including state-issued IDs, which are often prohibitively difficult for the poor and elderly to obtain. The book asks, will our children’s generation rise and continue the fight to protect this most basic and sacred of American rights? We can start by taking our children to the polls with us this November.

I found your blog post very insightful and I added “Lillian’s Right to Vote: A Celebration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965” to my list of books that I want for my future classroom. I also found the chronological structure of the book to be helpful in explaining the historical events. There are a lot of components to the Civil Rights Movement and the order is important. Are there any other Civil Rights Movement books you would recommend, besides “We Shall Overcome”?

I am so sorry that I initially missed this comment! Other favorites about the CRM are “We March” (also with illustrations by Shane W. Evans); Kadir Nelson’s presentation of MLK Jr’s “I Have a Dream Speech,” “Freedom Summer” by Deborah Wiles, and “The Story of Ruby Bridges.” For older children, “Voices of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer” and “Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom” are excellent.

Also, couple other previous posts you might find interesting:

–the Rosa Parks and MLK Jr. titles in this series both have great background info on the Civil Rights Movement (https://whattoreadtoyourkids.com/2016/11/17/introducing-sctivism-to-children/)

–This profile of Huntsville, Alabama is a tremendous way to frame the CRM for children (https://whattoreadtoyourkids.com/2015/02/19/activism-in-picture-books/)

Again, so sorry I missed you the first time around. Thanks for reading and commenting!

Excellent post! I just ordered a copy through Barnes and Noble. Unfortunately, it will not arrive before Tuesday.

Great! I hope you will enjoy it as much as we have.

[…] right to vote with the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment (although, as Jonah Winter’s powerful Lillian’s Right to Vote reveals, that was not the final word for African-American […]

[…] dramatic, pulsating illustrations by the great Shane W. Evans (you’ll remember how much we loved Lilian’s Right to Vote), but The Banana-Leaf Ball is a particularly special addition to the CitizenKid lineup. Based on a […]