Spring Break Recs: New Middle Grade for 8-13

March 14, 2024 § Leave a comment

I’m not sure I’ve ever counted down to Spring Break quite as fervently as I have this year. I need a break. My kids need a break. And we all need to get off screens. Cue a device-free week of puzzles, hikes, board games, and lots and lots of reading. At least, that’s my plan. (Happy to accept all ideas for how to convince my teens to go along without pitching a knock-down-drag-out fit.) Seriously, though, and I speak from experience: vacations can do wonders for resetting our children’s relationship with recreational reading.

If you have middle-grade readers, then they are in for a treat, because the start to 2024 has been one of the strongest I can remember. At the risk of jinxing our luck, it finally seems publishers have gotten the memo that today’s readers are looking for more action and less heaviness, shorter page counts and bigger servings of humor. There are some big crowd pleasers here. There are also some quieter, thoughtful reads that don’t sacrifice good pacing. Below, you’ll find mystery, thriller, horror, realistic contemporary fiction, historical fiction, and even a touch of sci fi. My word, all that and it isn’t but three months into the year! I wouldn’t be surprised if next year’s Newbery winner was in this list.

Let’s dig in. (And PSST: if you’re local and want to drop by Old Town Books, we have signed copies of several of these titles while supplies last. You can see me while you’re at it, as I’ll be there all day on Saturday, March 16 for our Books in Bloom event!)

« Read the rest of this entry »All The Awards for This One, Please (and a Jump on Black History Month)

January 26, 2023 § 2 Comments

Get ready to roll out the red carpet! The kid lit world is abuzz with the anticipation of the Youth Media Awards, which will be announced by the American Library Association this coming Monday. One of the frontrunners for multiple awards, including the Caldecott and Newbery Medals, not to mention the Coretta Scott King Award, is a picture book aimed at imparting a piece of devastating, powerful, and essential American history to elementary and middle school children—as well as to the parents and teachers that will hopefully share it with them. That it does so with unique artistry, searing lyricism, and the pulsating refrain of love is what distinguishes Choosing Brave: How Mamie Till-Mobley and Emmett Till Sparked the Civil Rights Movement (ages 8-12), written by Angela Joy, with artwork by debut illustrator, Janelle Washington, among its fellow 2022 contenders.

I was impressed with the book even before I read it aloud to my kids and husband earlier this week. But after speaking the poetic text aloud, after taking time to appreciate the motifs in the illustrations, after noting the questions that arose and the reflection that followed, I was floored. Actually, I was floored as much by what I gained in that moment as by what I had been missing.

As was the case Carole Boston Weatherford and Floyd Cooper’s Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre, a picture book that pulled in multiple awards last year, the experience of sharing Choosing Brave with my family was another stark reminder of the profound gaps in my own knowledge of Black history.

I was eleven years old when Black History Month was formalized. Even then, my education was cursory at best. Frederick Douglas and Harriet Tubman were taught alongside discussions of slavery. Rosa Parks, Ruby Bridges, and MLK were the only headliners I heard in conjunction with the Civil Rights Movement. I’m fairly positive The Great Migration wasn’t on my radar at all. Certainly not things like racial passing, until my good friend started writing her dissertation on it. Before last year, I thought the Tulsa Race Massacre concerned a running race.

It wasn’t until 2018, when I read Jewell Parker Rhodes’ middle-grade novel, Ghost Boys, that I began to think about the impact of the murder of Emmett Till, a name I previously associated only with tragedy. It wasn’t until Choosing Brave that I learned about the mother behind this fourteen-year-old boy. Here was someone who did something in her grief that was so smart, so courageous, that its ripple effects are still felt today. To leave these two—and countless others—out of our discussions of Black History is to deprive our country of a continued march towards progress. Especially when we’re still so far from the finish.

And so, for the umpteenth time, I am grateful for the children’s authors and illustrators who are telling these stories and telling them so well. These books are the best chance our children have for getting a robust history of this country—assuming their access to these stories isn’t restricted (and that’s no easy feat these days). But the best part? In partaking in these stories, our kids can bring us along for the ride.

(Linking a few past posts on Black History here, here, and here, while I’m feeling fired up.)

Let’s take a look at Choosing Brave, which clocks in at a whopping 64 pages and would deserve any accolades it receives next Monday, for words and art. Angela Joy’s evocative text, underscored with repetition, moves backwards and forward in time to tell a story of mother and son that’s much more than the tragedy at its heart. And Janelle Washington’s black cut-paper collages, notable for their silhouetted forms and strategically-placed pops of color, the latter created with tissue paper, assume an iconic, almost religious feel. (“I just had to pray and brave it,” Mamie Till Washington is quoted as saying in the book’s epigraph.) In fact, in a superior act of bookmaking, the pages themselves have a kind of waxy, glazy finish, giving the art the effect of stained glass in a church, at once confined and luminous.

« Read the rest of this entry »When A Book Comes Along for the Field Trip

January 20, 2022 § 2 Comments

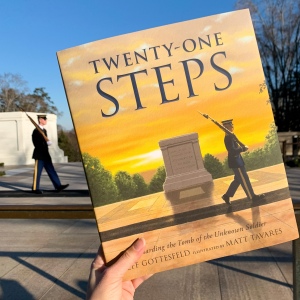

There was no shortage of grumbling when, one morning over winter break, I announced we were going to Arlington National Cemetery, a ten minute drive from our house.

“But we’ve been there a million times,” my son complained.

“You’ve been there exactly once,” I responded. “Plus, my great-grandfather was a Colonel in World War One, and he’s buried there.”

“We know, because you tell us all the time,” my daughter interjected, not to be outdone by her brother.

“Well, we’ve had a Covid Christmas and we need somewhere to go that’s outside, so that’s that,” I issued, like the authoritarian parent I am.

In my 14-year parenting tenure, there has never been an outing I haven’t been able to improve with a children’s book. In this case, I’d had one tucked away for almost a year. I knew the kids would come around. They always come around.

Jeff Gottesfeld’s Twenty-One Steps: Guarding the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, majestically illustrated by Matt Tavares (don’t count him out for a Caldecott), takes us behind the scenes of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier—indisputably the most fascinating part of Arlington Cemetery. No one can help but be awestruck upon beholding the discipline, concentration, and precision of the sentinel guards who keep vigil there, every moment of every day, 365 days a year, in every type of weather.

Especially if you’ve had the chance to read Twenty-One Steps immediately before.

Which our family had, while seated in front of my great-grandparents’ gravestone, under a brilliantly blue December sky, surrounded by thousands of wreaths placed there for the holidays. We read while we waited for the top of the hour, when we headed over to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to watch the changing of the guard.

« Read the rest of this entry »Seizing His Shot: A Black History Month Post

February 4, 2021 § 1 Comment

(Check out previous years’ picks for Black History Month here, here, and here. I’ll also be sharing other new titles celebrating Black history all month long over on Instagram.)

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it ‘till the cows come home: picture books aren’t just for little kids! Keeping picture books alive and well at home, even after our kids are reading independently, means not only continuing to expose them to arresting art and sensational storytelling, it means piquing their interest about a range of subjects they might not seek out on their own. After all, it can be much less intimidating to pick up a picture book than a chapter book, especially on a subject you don’t know much about.

I love a picture book that sneaks in a history lesson without ever feeling instructional. One of my favorite picture book biographies published last year, Above the Rim: How Elgin Baylor Changed Basketball (Ages 6-10), also happens to be an excellent primer on the Civil Rights Movement. But you’d expect nothing left from the all-star team of Sibert Medalist, Jen Bryant, and two-time Coretta Scott King Medalist, Frank Morrison.

Jen Bryant is best known for her picture book biographies of artists and writers (A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams is a favorite), but she was drawn to NBA Hall of Famer, Elgin Baylor, because in addition to his undeniable talent on the court, he also fundamentally changed the game itself. “Artists change how we see things, how we perceive human limits, and how we define ourselves and our culture,” Bryant writes in the Author’s Note at the end of the book. By this definition, Elgin Baylor—who as one of the first professional African-American players broke nearly every tradition in the sport—was every bit the artist. And Bryant uses her love of language to make his story leap off the page.

In that vein, too, it seems fitting that Frank Morrison should illustrate the basketball icon, using his signature unconventional style of oil painting that distorts and elongates the human figure, giving it both elasticity and a larger-than-life aura. (Morrison illustrates one of my other favorite 2020 picture book biographies, R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul.) Morrison’s art in Above the Rim is kinetic; it buzzes like the energy on a court. But it’s also dramatic, moving from shadow into light, much like the broader social movement in which Elgin Baylor found himself a quiet but powerful participant.

Should I mention my ten-year-old daughter (mourning the loss of basketball in this pandemic) adores this book and reaches for it often?

« Read the rest of this entry »Emily Dickinson: Perfect Reading for a Pandemic?

September 24, 2020 § 2 Comments

Not many people know this, but my daughter is named after Emily Dickinson. (Well, and the heroine of L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon.) I didn’t fall for Emily Dickinson’s poetry until I got to college, when I fell hard and fast and ended up featuring her poems in no fewer than seven essays, including my Senior Thesis. I had never been a big poetry lover, but there was something about the compactness of her poems which fascinated me. So much meaning was packed into such few words. And even then, the meaning was like an ever-shifting target, evolving with every reading.

Not many people know this, but my daughter is named after Emily Dickinson. (Well, and the heroine of L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon.) I didn’t fall for Emily Dickinson’s poetry until I got to college, when I fell hard and fast and ended up featuring her poems in no fewer than seven essays, including my Senior Thesis. I had never been a big poetry lover, but there was something about the compactness of her poems which fascinated me. So much meaning was packed into such few words. And even then, the meaning was like an ever-shifting target, evolving with every reading.

To read Emily Dickinson is to contemplate universal truths.

Apart from reading Michael Bedard and Barbara Cooney’s 1992 picture book, Emily, I hadn’t had much occasion talk to my own Emily about her namesake. But that changed last spring, when my Emily started writing poetry of her own. Nothing about virtual learning was working for her, until her teachers started leading her and her classmates in poetry writing. Suddenly, my daughter couldn’t jot down poems fast enough, filling loose sheets of paper before designating an orange journal for the occasion. She wrote poems for school, for fun, and for birthday cards. It didn’t matter that they weren’t going to win awards for originality; what mattered was that she had found a means of self-expression during a stressful, beguiling time.

Jennifer Berne’s On Wings of Words: The Extraordinary Life of Emily Dickinson (Ages 7-10), stunningly illustrated by Becca Stadtlander, could not have entered the world at a more perfect time. It opens a dialogue, not only about Dickinson’s unconventional life, but about her poems themselves. At a time when a pandemic has prompted many of us and our children to turn inward, this picture book is less a traditional biography than an homage to the rich interior life developed by this extraordinary poet and showcased in her poetry.

Moving Past Color-Blindness

June 25, 2020 § 2 Comments

I have been drafting this post in my head for two weeks, terrified to put pen to paper for the dozens of ways I will certainly mis-step. Raising children dedicated to equity and justice has always been important to me—if you’ve been following my blog, you’ll recognize it as a frequent theme here—but only lately have I pushed myself to consider the ways my own privilege, upbringing, and anxiety have stood in the way of that. It is clear that I cannot raise my children to be antiracist if I am not prepared to do the work myself.

I have been drafting this post in my head for two weeks, terrified to put pen to paper for the dozens of ways I will certainly mis-step. Raising children dedicated to equity and justice has always been important to me—if you’ve been following my blog, you’ll recognize it as a frequent theme here—but only lately have I pushed myself to consider the ways my own privilege, upbringing, and anxiety have stood in the way of that. It is clear that I cannot raise my children to be antiracist if I am not prepared to do the work myself.

When my daughter was three, I brought her to the pediatrician’s office for a rash. As we sat in the waiting room, watching and remarking on the colorful fish swimming in the aquarium, my daughter suddenly turned to me. “Mommy, is the nurse going to be black-skinned?”

Embarrassment rose in my cheeks. “Oh honey, I’m sure any nurse here is a good nurse. Let’s not—”

Her interrupting voice rose about ten decimals. “Because I am not taking off my clothes for anyone with black skin!”

Just typing this, my hands are shaking. I am back, seven years ago, in that waiting room, aware of all eyes upon us. Aware of the brown-skinned couple with their newborn baby sitting directly across from us. This can’t be happening, I thought. This can’t be my child. She goes to a preschool with a multicultural curriculum. We read books with racially diverse characters. She plays with children who look different than her. Shock, outrage, and humiliation flooded every inch of my being.

Caught off guard and determined to rid myself of my own shame, I fell into a trap familiar to many white parents. For starters, I came down hard on her. I took my shame and put it squarely onto her. I was going to stop this talk immediately. I was going to prove to everyone listening that this was unacceptable behavior in our family. I was going to make it…all about me.

“Stop it!” I said firmly. “We do not say things like that.” Then, I started rambling about how we shouldn’t judge people by how they look, how underneath skin color we’re all the same, how we’re all one big human family, and so on. You know: the speech. The color-blind speech. The one where white parents tell their children to look past skin tone to the person underneath. The one where we imply that because skin color is something we’re born with, something “accidental,” we shouldn’t draw attention to it. The one where we try and push on our children a version of the world we’d like to inhabit, as opposed to the one we actually do.

My three year old was observing—albeit not kindly or subtly—that not everyone looked the way she did. And she wasn’t sure if that was OK. She was scared. She was uncomfortable. Because we weren’t talking about skin tone or race with her at home, because our conversations (however well-intentioned) steered mainly towards platitudes of kindness and acceptance, she had begun to internalize the racial assumptions around her. She had used the descriptor “black-skinned,” I later realized, whereas if she had simply been observing skin tone, she would have said brown skin or dark skin. The word she chose was a reference to race. A loaded word. Something she had heard. Something she didn’t understand. Something she was beginning to associate with something less than.

We don’t want our children to use race to make judgments about people, so we’d rather them dismiss race completely. Except, in a society where race is embedded into nearly every policy and practice, it is impossible not to see race. So instead, what we are really communicating to our young children is, I know you notice these differences, but I don’t want you to admit it. (Including to yourself). Good white liberal children don’t talk about their black and brown friends as being different from them. Even more problematic, good white liberal children love their black and brown friends in spite of these differences.

Concluding Black History Month on the Train

February 27, 2020 Comments Off on Concluding Black History Month on the Train

Every year, once in the fall and once in the spring, I take each of my children on a mommy-and-me trip to New York City for a long weekend in the city where I grew up. We board the train in Alexandria, Virginia and make stops in Washington, D.C.; Baltimore, Maryland; Newark, Delaware; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and, finally, New York City, Penn Station. My kids have come to enjoy the train ride almost as much as the destination itself, glancing up from their books to watch the changing scenery speeding by—there is something innately lolling and contemplative about train travel—and anticipating the stops to come.

Every year, once in the fall and once in the spring, I take each of my children on a mommy-and-me trip to New York City for a long weekend in the city where I grew up. We board the train in Alexandria, Virginia and make stops in Washington, D.C.; Baltimore, Maryland; Newark, Delaware; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and, finally, New York City, Penn Station. My kids have come to enjoy the train ride almost as much as the destination itself, glancing up from their books to watch the changing scenery speeding by—there is something innately lolling and contemplative about train travel—and anticipating the stops to come.

These same train stops come to life against an important and fascinating historical backdrop in Overground Railroad (Ages 4-9), a new picture book by superstar husband-and-wife team Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome, whose Before She Was Harriet I praised around this same time last year. “Isn’t it supposed to be “Underground Railroad?” my daughter asked, when I picked up the book to read it to her. Admittedly, I was equally stumped. As the Author’s Note explains, most people are familiar with the covert network known as the Underground Railroad, which assisted runaway slaves on their journey to the North, usually on foot. Lesser known but often equally secretive, the Overground Railroad refers to the train and bus routes traveled by millions of black Americans during the Great Migration, a time when former slaves opted to free themselves from the limitations and injustices of sharecropping to seek out better employment and educational opportunities in the North. Faced with the threat of violence from the owners of these tenant farms, who relied on the exploitation of sharecroppers for their livelihood, those who escaped often had to do so under cover of night.

Taking Up Space (A Black History Month Post)

February 21, 2019 § 2 Comments

In her modern dance classes, my daughter cherishes above all the few minutes devoted to “sparkle jumps.” One by one, the dancers crisscross the studio at a run. As each one reaches the middle, she explodes into a leap, arms reaching up and out, head tall, like the points of a star. For one perfect moment, my daughter takes up as much space as her little body will allow.

In her modern dance classes, my daughter cherishes above all the few minutes devoted to “sparkle jumps.” One by one, the dancers crisscross the studio at a run. As each one reaches the middle, she explodes into a leap, arms reaching up and out, head tall, like the points of a star. For one perfect moment, my daughter takes up as much space as her little body will allow.

“I love watching you take up space,” I tell her. « Read the rest of this entry »

Hello, Awards Time!

January 31, 2019 § 1 Comment

This past Monday, I watched and cheered at my computer as the American Library Association’s Youth Media Awards were announced (more fun than the Oscars for #kidlit crazies like me). Most parents are familiar with the Caldecott and Newbery medals, but there are quite a few other awards distributed, many to recognize racial, cultural, and gender diversity. Overall, I was pleased to see many of my 2018 favorites come away with shiny gold and silver stickers. At the end of today’s post, I’ll include some of these titles, along with links to what I’ve written about them.

This past Monday, I watched and cheered at my computer as the American Library Association’s Youth Media Awards were announced (more fun than the Oscars for #kidlit crazies like me). Most parents are familiar with the Caldecott and Newbery medals, but there are quite a few other awards distributed, many to recognize racial, cultural, and gender diversity. Overall, I was pleased to see many of my 2018 favorites come away with shiny gold and silver stickers. At the end of today’s post, I’ll include some of these titles, along with links to what I’ve written about them.

Today, I want to devote some space to Sophie Blackall’s Hello Lighthouse, which came away with the Randolph Caldecott Medal, for the “most distinguished American picture book for children.” (It’s actually the second Caldecott for Blackall, who won three years ago for this gem). Hello Lighthouse (Ages 6-9) is one of my very favorites from last year; and yet, I haven’t talked about it until now. Why is that? Perhaps because the art in this book is so endlessly fascinating, my observations continue to evolve with every read. I suppose I’ve been at a loss for words. « Read the rest of this entry »

Putting One Book in Front of the Other

October 12, 2018 § 2 Comments

My children have heard a lot about the Supreme Court in recent weeks—mostly delivered via their parents and mostly accompanied by outcries of frustration and despair. Still, as much as I want them to understand my concerns with what today’s political actions reveal about the values of our leadership, I also don’t want my discourse to taint (at least, not permanently) the way they view our government’s enduring institutions.

My children have heard a lot about the Supreme Court in recent weeks—mostly delivered via their parents and mostly accompanied by outcries of frustration and despair. Still, as much as I want them to understand my concerns with what today’s political actions reveal about the values of our leadership, I also don’t want my discourse to taint (at least, not permanently) the way they view our government’s enduring institutions.

In short, our family needed a pick-me-up. I needed both to remind myself and to teach my children about the Supreme Court Justices who, right now, are fighting for fairness under the law—and who arrived there with poise, valor, humanity, and moral clarity. « Read the rest of this entry »

It has been said that the only two certainties in life are death and taxes, but—at least, while quarantined—I can now add a third. Every morning for the past two months, the same conversation has transpired as soon as the breakfast dishes are cleared, around 8:15am.

It has been said that the only two certainties in life are death and taxes, but—at least, while quarantined—I can now add a third. Every morning for the past two months, the same conversation has transpired as soon as the breakfast dishes are cleared, around 8:15am.

Our children are blessed to be growing up at a time when kids’ nonfiction is being published almost as rapidly as fiction—and with as much originality! On this comprehensive list you’ll find new books for a range of ages on a range of subjects, including geology, biology, astronomy, art, World War Two, American History, survival, current events…and even firefighting. (Psst, I’m saving nonfiction graphic novels for the next post, just to give you something to look forward to.) Hooray for a fantastic year for nonfiction!

Our children are blessed to be growing up at a time when kids’ nonfiction is being published almost as rapidly as fiction—and with as much originality! On this comprehensive list you’ll find new books for a range of ages on a range of subjects, including geology, biology, astronomy, art, World War Two, American History, survival, current events…and even firefighting. (Psst, I’m saving nonfiction graphic novels for the next post, just to give you something to look forward to.) Hooray for a fantastic year for nonfiction!