All The Awards for This One, Please (and a Jump on Black History Month)

January 26, 2023 § 2 Comments

Get ready to roll out the red carpet! The kid lit world is abuzz with the anticipation of the Youth Media Awards, which will be announced by the American Library Association this coming Monday. One of the frontrunners for multiple awards, including the Caldecott and Newbery Medals, not to mention the Coretta Scott King Award, is a picture book aimed at imparting a piece of devastating, powerful, and essential American history to elementary and middle school children—as well as to the parents and teachers that will hopefully share it with them. That it does so with unique artistry, searing lyricism, and the pulsating refrain of love is what distinguishes Choosing Brave: How Mamie Till-Mobley and Emmett Till Sparked the Civil Rights Movement (ages 8-12), written by Angela Joy, with artwork by debut illustrator, Janelle Washington, among its fellow 2022 contenders.

I was impressed with the book even before I read it aloud to my kids and husband earlier this week. But after speaking the poetic text aloud, after taking time to appreciate the motifs in the illustrations, after noting the questions that arose and the reflection that followed, I was floored. Actually, I was floored as much by what I gained in that moment as by what I had been missing.

As was the case Carole Boston Weatherford and Floyd Cooper’s Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre, a picture book that pulled in multiple awards last year, the experience of sharing Choosing Brave with my family was another stark reminder of the profound gaps in my own knowledge of Black history.

I was eleven years old when Black History Month was formalized. Even then, my education was cursory at best. Frederick Douglas and Harriet Tubman were taught alongside discussions of slavery. Rosa Parks, Ruby Bridges, and MLK were the only headliners I heard in conjunction with the Civil Rights Movement. I’m fairly positive The Great Migration wasn’t on my radar at all. Certainly not things like racial passing, until my good friend started writing her dissertation on it. Before last year, I thought the Tulsa Race Massacre concerned a running race.

It wasn’t until 2018, when I read Jewell Parker Rhodes’ middle-grade novel, Ghost Boys, that I began to think about the impact of the murder of Emmett Till, a name I previously associated only with tragedy. It wasn’t until Choosing Brave that I learned about the mother behind this fourteen-year-old boy. Here was someone who did something in her grief that was so smart, so courageous, that its ripple effects are still felt today. To leave these two—and countless others—out of our discussions of Black History is to deprive our country of a continued march towards progress. Especially when we’re still so far from the finish.

And so, for the umpteenth time, I am grateful for the children’s authors and illustrators who are telling these stories and telling them so well. These books are the best chance our children have for getting a robust history of this country—assuming their access to these stories isn’t restricted (and that’s no easy feat these days). But the best part? In partaking in these stories, our kids can bring us along for the ride.

(Linking a few past posts on Black History here, here, and here, while I’m feeling fired up.)

Let’s take a look at Choosing Brave, which clocks in at a whopping 64 pages and would deserve any accolades it receives next Monday, for words and art. Angela Joy’s evocative text, underscored with repetition, moves backwards and forward in time to tell a story of mother and son that’s much more than the tragedy at its heart. And Janelle Washington’s black cut-paper collages, notable for their silhouetted forms and strategically-placed pops of color, the latter created with tissue paper, assume an iconic, almost religious feel. (“I just had to pray and brave it,” Mamie Till Washington is quoted as saying in the book’s epigraph.) In fact, in a superior act of bookmaking, the pages themselves have a kind of waxy, glazy finish, giving the art the effect of stained glass in a church, at once confined and luminous.

« Read the rest of this entry »Poetry to Re-Frame Our World

April 28, 2022 § 2 Comments

You didn’t actually think I’d let National Poetry Month go without loving on a few new poetry books, did you? Now wait. I know poetry scares some of us—or scares our kids—but, like with everything from green vegetables to voting, early and often are the keys to success. National Poetry Month will always be a great excuse to infuse our shelves with a new title or three—and maybe re-visit a few that have been languishing. Getting kids comfortable around poetry means deepening their relationship with language, especially figurative language, which will carry them far in any creative pursuit, not to mention the non-linear thinking increasingly rewarded in business.

My greatest parenting win around the subject of poetry remains the year we read a poem from this gorgeous anthology every morning over breakfast. I heartily recommend forgoing conversation for poetry in the mornings! (I hear caffeine’s good, too.) When a new title came out in this same series last fall, I had high hopes we’d rekindle this ritual, but with my teen out the door so much earlier than his sister, this hasn’t happened.

So, consider today’s post as much about my own need to recommit to poetry—something my kids rarely gravitate towards without a nudge—as about inspiring you to do the same. In that vein, I’ve got two vastly different new poetry picture books: one for the preschool crowd and the other for elementary kids. The first is an absolute delight to read aloud, while the second is perhaps better left for independent readers to contemplate privately.

Take Off Your Brave: The World Through the Eyes of a Preschool Poet (Ages 3-6) is a collection of poems written by an actual four-year-old boy named Nadim, using his Mom as a “dictaphone.” Talk about making poetry feel accessible to kids! Here, Nadim gives us a window into the way he sees the world: his dream school, his best things, his “scared-sugar” feelings. Each poem is playfully brought to life by award-winning illustrator, Yasmeen Ismail.

Ted Kooser and Connie Wanek’s Marshmallow Clouds: Two Poets at Play Among Figures of Speech (Ages 8-12, though adults will love this, too) is one of the most simultaneously quirky and powerful poetry collections I’ve encountered, a look at what happens when we unleash our imaginations on the natural elements around us. And it’s as much an art book as a poetry book! Artist Richard Jones is already getting Caldecott buzz for his gorgeous, full-bleed illustrations that accompany each of the 28 poems.

Both of these special books speak to the magic of poetry: the way it enables us to process the creative, off-kilter, silly, sometimes contradictory ways we see or experience the world. For as many hang-ups as we have around poetry—its perceived obtuseness, its relegation to the realm of intellectuals—these books remind us that poetry is as simple as conjuring a moment and penning it in a non-traditional way. These poems celebrate the poets in all of us.

« Read the rest of this entry »When A Book Comes Along for the Field Trip

January 20, 2022 § 2 Comments

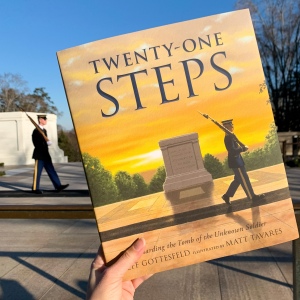

There was no shortage of grumbling when, one morning over winter break, I announced we were going to Arlington National Cemetery, a ten minute drive from our house.

“But we’ve been there a million times,” my son complained.

“You’ve been there exactly once,” I responded. “Plus, my great-grandfather was a Colonel in World War One, and he’s buried there.”

“We know, because you tell us all the time,” my daughter interjected, not to be outdone by her brother.

“Well, we’ve had a Covid Christmas and we need somewhere to go that’s outside, so that’s that,” I issued, like the authoritarian parent I am.

In my 14-year parenting tenure, there has never been an outing I haven’t been able to improve with a children’s book. In this case, I’d had one tucked away for almost a year. I knew the kids would come around. They always come around.

Jeff Gottesfeld’s Twenty-One Steps: Guarding the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, majestically illustrated by Matt Tavares (don’t count him out for a Caldecott), takes us behind the scenes of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier—indisputably the most fascinating part of Arlington Cemetery. No one can help but be awestruck upon beholding the discipline, concentration, and precision of the sentinel guards who keep vigil there, every moment of every day, 365 days a year, in every type of weather.

Especially if you’ve had the chance to read Twenty-One Steps immediately before.

Which our family had, while seated in front of my great-grandparents’ gravestone, under a brilliantly blue December sky, surrounded by thousands of wreaths placed there for the holidays. We read while we waited for the top of the hour, when we headed over to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to watch the changing of the guard.

« Read the rest of this entry »Earth Day! New Non-Fiction Celebrating Our Planet

April 22, 2021 Comments Off on Earth Day! New Non-Fiction Celebrating Our Planet

Every year on Earth Day, I smile thinking about my son at age four, who looked up at me with his big brown eyes and asked, “Mommy, aren’t we supposed to care about the Earth every day?” Yes, my boy. Same with Black history and women’s history and all the rest of these annual celebrations. But it sure is nice, now and then, to be nudged to think about our home libraries, about how we might freshen them up in a way that leads to better, richer dialogues with our children. After all, books bring with them such marvelous reminders of what a special, precious gift this planet is.

Today, I’m sharing three new non-fiction titles, targeting a range of ages. Each delivers a wealth of information—be it flowers, trees, or climate change—in clever, arresting, beautiful presentations. These aren’t the non-fiction books of our childhood, with tiny type and dizzying details. They’re a testament to a new way of presenting scientific content to kids, one which doesn’t sacrifice visual ingenuity or narrative appeal. They’re books we parents won’t get tired reading. In fact, we’re likely to learn things alongside our children. What better way to model caring for our planet than showcasing our own curiosity and discovery?

« Read the rest of this entry »Seizing His Shot: A Black History Month Post

February 4, 2021 § 1 Comment

(Check out previous years’ picks for Black History Month here, here, and here. I’ll also be sharing other new titles celebrating Black history all month long over on Instagram.)

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it ‘till the cows come home: picture books aren’t just for little kids! Keeping picture books alive and well at home, even after our kids are reading independently, means not only continuing to expose them to arresting art and sensational storytelling, it means piquing their interest about a range of subjects they might not seek out on their own. After all, it can be much less intimidating to pick up a picture book than a chapter book, especially on a subject you don’t know much about.

I love a picture book that sneaks in a history lesson without ever feeling instructional. One of my favorite picture book biographies published last year, Above the Rim: How Elgin Baylor Changed Basketball (Ages 6-10), also happens to be an excellent primer on the Civil Rights Movement. But you’d expect nothing left from the all-star team of Sibert Medalist, Jen Bryant, and two-time Coretta Scott King Medalist, Frank Morrison.

Jen Bryant is best known for her picture book biographies of artists and writers (A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams is a favorite), but she was drawn to NBA Hall of Famer, Elgin Baylor, because in addition to his undeniable talent on the court, he also fundamentally changed the game itself. “Artists change how we see things, how we perceive human limits, and how we define ourselves and our culture,” Bryant writes in the Author’s Note at the end of the book. By this definition, Elgin Baylor—who as one of the first professional African-American players broke nearly every tradition in the sport—was every bit the artist. And Bryant uses her love of language to make his story leap off the page.

In that vein, too, it seems fitting that Frank Morrison should illustrate the basketball icon, using his signature unconventional style of oil painting that distorts and elongates the human figure, giving it both elasticity and a larger-than-life aura. (Morrison illustrates one of my other favorite 2020 picture book biographies, R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul.) Morrison’s art in Above the Rim is kinetic; it buzzes like the energy on a court. But it’s also dramatic, moving from shadow into light, much like the broader social movement in which Elgin Baylor found himself a quiet but powerful participant.

Should I mention my ten-year-old daughter (mourning the loss of basketball in this pandemic) adores this book and reaches for it often?

« Read the rest of this entry »2020 Gift Guide: My Favorite Picture Book for the Elementary Crowd

October 22, 2020 § 3 Comments

As a nervous flyer, I never thought I’d write this, but I really miss getting on airplanes. Traveling is something I’ve never taken for granted, but I’m not sure I realized just how much I crave it until it wasn’t an option. I miss stepping off a plane, filled with the adrenaline of adventures ahead. I miss unfamiliar restaurants and museums. I miss natural wonders so far from my everyday environs it’s hard to believe they’re on the same planet. I miss squishing into a single hotel room, each of us climbing into shared beds after a day of sensory overload and, one by one, closing our eyes. I can’t wait until we can travel again.

In the meantime, we look to books to fuel our longing to see the world, to keep alive this thirst for the unfamiliar and the undiscovered. No picture book this year delivers on this promise quite like Girl on a Motorcycle (Ages 5-9), by Amy Novesky, illustrated by Julie Morstad, based on the actual adventures of Anne-France Dautheville, the first woman to ride a motorcycle around the world alone. From her hometown of Paris to Canada, India, Afghanistan, Turkey, and other exotic destinations, we travel alongside this inquisitive, fiercely independent girl as she heeds the call of the open road.

Morstad is no stranger to illustrating picture book biographies—It Began With a Page: How Gyo Fujikawa Drew the Way made last year’s Gift Guide—and part of her remarkable talent stems from adapting her illustrative style to the subject at hand, while still creating a look and feel entirely her own. In Girl on a Motorcycle, Morstad infuses a ’70s palette of glowy browns and moody mauves onto the dusty backdrops of the Middle East, the dense evergreens of the Canadian countryside, and the ethereal sunrises. Additionally, Morstad gives the protagonist herself a kind of badass glamour every bit as alluring as the scenery itself. How can we not fall for someone who packs lipstick next to a “sharp knife”? It’s as if Vogue jumped on the back of a motorcycle, slept in a tent at night, and made friends with locals along the way.

« Read the rest of this entry »Emily Dickinson: Perfect Reading for a Pandemic?

September 24, 2020 § 2 Comments

Not many people know this, but my daughter is named after Emily Dickinson. (Well, and the heroine of L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon.) I didn’t fall for Emily Dickinson’s poetry until I got to college, when I fell hard and fast and ended up featuring her poems in no fewer than seven essays, including my Senior Thesis. I had never been a big poetry lover, but there was something about the compactness of her poems which fascinated me. So much meaning was packed into such few words. And even then, the meaning was like an ever-shifting target, evolving with every reading.

Not many people know this, but my daughter is named after Emily Dickinson. (Well, and the heroine of L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon.) I didn’t fall for Emily Dickinson’s poetry until I got to college, when I fell hard and fast and ended up featuring her poems in no fewer than seven essays, including my Senior Thesis. I had never been a big poetry lover, but there was something about the compactness of her poems which fascinated me. So much meaning was packed into such few words. And even then, the meaning was like an ever-shifting target, evolving with every reading.

To read Emily Dickinson is to contemplate universal truths.

Apart from reading Michael Bedard and Barbara Cooney’s 1992 picture book, Emily, I hadn’t had much occasion talk to my own Emily about her namesake. But that changed last spring, when my Emily started writing poetry of her own. Nothing about virtual learning was working for her, until her teachers started leading her and her classmates in poetry writing. Suddenly, my daughter couldn’t jot down poems fast enough, filling loose sheets of paper before designating an orange journal for the occasion. She wrote poems for school, for fun, and for birthday cards. It didn’t matter that they weren’t going to win awards for originality; what mattered was that she had found a means of self-expression during a stressful, beguiling time.

Jennifer Berne’s On Wings of Words: The Extraordinary Life of Emily Dickinson (Ages 7-10), stunningly illustrated by Becca Stadtlander, could not have entered the world at a more perfect time. It opens a dialogue, not only about Dickinson’s unconventional life, but about her poems themselves. At a time when a pandemic has prompted many of us and our children to turn inward, this picture book is less a traditional biography than an homage to the rich interior life developed by this extraordinary poet and showcased in her poetry.

Rich in Stories

May 7, 2020 § 4 Comments

For many of us following stay-at-home orders, social media is a welcome lifeline to the outside world. And yet, its lure can be as powerful as its trapping. If occasionally I used to fall down the rabbit hole of comparing my children’s accomplishments to those paraded out on Facebook, I now find myself in weaker moments comparing houses. We may be leading similar lives—working, schooling, eating at home—but our backdrops are wildly different. Maybe I’d be going less crazy if I looked out my window and saw mountains. Sure would be nice to have a swimming pool in my backyard. Sure would be nice to have any backyard. Oh man, are they at their river house right now? I’m sure I could homeschool better if we had a creek.

For many of us following stay-at-home orders, social media is a welcome lifeline to the outside world. And yet, its lure can be as powerful as its trapping. If occasionally I used to fall down the rabbit hole of comparing my children’s accomplishments to those paraded out on Facebook, I now find myself in weaker moments comparing houses. We may be leading similar lives—working, schooling, eating at home—but our backdrops are wildly different. Maybe I’d be going less crazy if I looked out my window and saw mountains. Sure would be nice to have a swimming pool in my backyard. Sure would be nice to have any backyard. Oh man, are they at their river house right now? I’m sure I could homeschool better if we had a creek.

Of course, these thoughts are inane. Inanely unproductive. Inanely indulgent. At no time for my generation has it been more of a blessing to have our health and a roof over our heads. Not to mention money for food and ample time to steer our children through these rocky waters.

Still, I would be lying if I said there aren’t cracks in my resolve to be gracious and mindful.

With our recent move, our living space has been significantly downsized. I can’t spit without hitting another person. Heck, I can hardly do anything without being watched or whined at. My husband gave me grief for packing up no fewer than four boxes of books to bring with us to these temporary digs. But you know what? We are rich in stories. We have stories painted with breathtaking backdrops, stories which quicken our pulse or tug at our heart or seduce us with beauty…all from the cozy confines of our couch. Some days, I look at the piles of books haphazardly lying around and I think, Why does no one clean up? Most days, I look at them and think, We are the luckiest.

One need look no further than Aesop’s fables for proof that stories have long been offering hope in turbulent times. Tales like “The Lion and the Mouse” (or my favorite as a parent, “The Boy Who Cried Wolf”) have been told and retold around the world for 2,500 years. Until now, I didn’t realize that the allegedly true story of Aesop himself—a slave in Ancient Greece who earned his freedom through storytelling—also bears telling, lending meaningful context to Aesop’s beguiling fables while offering proof that stories are richer than gold.

Ian Lendler’s 63-page trove, The Fabled Life of Aesop (Ages 5-9), luminously illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski, is not your typical picture book biography. It’s more of an anthology of fables encased in a broader, biographical context. Like an onion, each turn of the page reveals another layer of story and art, the sum of which is one of the most spellbinding books of 2020. It can be read in a single sitting or paged through out of order. If we’re talking about losing ourselves in the sublime for a time, this is just the ticket.